Boundary County

Section 5

Hazard Profiles – Wildland / Urban Interface Fire

|

|

Definition, Description and Potential

Damage Of the natural hazards that occur in Boundary County, forest

fires are the most frequently occurring events.

A high proportion of these fires occur in or near human habitations.

Forest fires occurring in the county have historically covered very large

areas of land. Under the right

conditions of fire-weather and dryness of forest fuels, a fire in the wild land

urban interface would have disastrous consequences.

The costs of fighting large wildland fires such as occur in Boundary

County are very high, and these costs go up exponentially when the fire is in or

near the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI). Potential

losses from an event that destroys many structures, and perhaps involves loss of

human life, are extremely high.

In 2003, Boundary County

contracted with Inland Forest Management, Inc. (IFM) for the completion of a Wildland/Urban

Interface Fire Mitigation Plan. This

plan included numerous considerations for wild land fire mitigation including

risk assessment, public involvement, appropriate strategies and priorities for

mitigation work. Only highlights

from the fire plan are included within this All

Hazards Mitigation Plan, however, the entire Wildland Fire Mitigation Plan

is considered incorporated by reference.

Brief Fire History

Large forest fires have played a prominent role in the forests of

Boundary County since the end of the last glacial period.

Most forest types in the county show a history of large stand-replacement

fires that often leave burn patterns of several thousand acres on the landscape.

Large fires have been caused both by lightening and humans.

Large fires have been documented

since 1900, many of which have occurred in present day wildland/urban interface.

In 1910, a large fire burned along the Katka face and into Montana.

The Hellroaring fire burned from Round Prairie to the top of Queen

Mountain in 1926. In 1931, the Deer

Creek fire started in Lower Deer Creek and burned north and east into the Yaak

River drainage in Canada.

Two large fires occurred in the

Selkirk Mountains, Sundance and Trapper Peak, in 1967.

These fires burned outside urban areas, but during its historic run, the

Sundance fire pelted the Kootenai River valley with firebrands.

It is perhaps only by good luck that this fire did not cause a disastrous

wildland/urban interface fire somewhere in the Kootenai Valley.

In the past 18 years, an average 23.4 wildfires per year have been fought on

USFS protection lands and 26 wildfires per year have been fought on IDL

protection lands. Some of the fires

on USFS protection and virtually all of the fires on IDL protection either had

the potential or actually posed a threat to the WUI. Under conditions conducive to high rates of spread, or long

distance spotting, IDL studies show that a fire can threaten individual and/or

groups of homes in the time between ignition and response by firefighters.

This brief summary of some of

the larger recent fires in the county and average fire occurrence in the county

shows why fire managers have had a long-standing concern for the protection of

life and property within the entire county.

Fire history, existing fuel types, and the expansion of dwellings further

into the wildland setting all suggest that there is a need to assess and address

the potential for future disastrous fires.

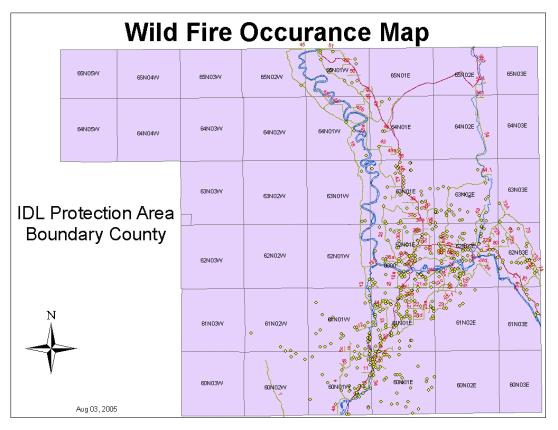

Map 5-1

WUI Mitigation Needs

The Boundary County Idaho Wildland/Urban Interface Fire Mitigation Plan

defined the type of work needed to reduce the potential for losses of life and

property from fires in the WUIF. The

goal of that plan is to create defensible space (safe area for fire fighters)

and survivable space (sufficient reduction in fire behavior to help the building

survive) around any building that is selected for fuel mitigation work.

To create defensible/survivable space, natural forest fuels are modified

to reduce the intensity of fire that would occur if they were to burn.

Fuel reduction is done at least 100 feet out from the perimeter of the

building (if property boundaries allow). Fuel

treatment involves the following general kinds of work activities:

1.

Removing most shrubs and conifer saplings and pole timber within 30 feet

of the building.

2.

Thinning conifer saplings to the perimeter boundary so that the crowns

are not touching and the trees have room to grow without again becoming

interlocking.

3.

Pruning all trees within the treatment area to one-half live crown or to

the point that remaining foliage is at least 10 feet off the ground.

4.

Pruning tall conifers within 15 feet of buildings to the point that no

foliage is below the eave line.

5.

Mowing most shrubs and brush to the perimeter boundary.

6.

Thinning trees whose crowns are in the main canopy so that the canopy is

not continuous and is incapable of sustaining a crown fire.

7.

Piling and burning, or chipping and spreading residues from the thinning,

mowing and pruning activities.

Priorities for Fuel Treatment The Boundary County Idaho Wildland/Urban Interface Fire

Mitigation Plan established priorities for fuel treatment work to reduce the

risk to loss of life and property in the event of wild land fires in the county.

As recommended in the plan, a fuel reduction program (called Fire Safe)

has been in place since 2003, with accomplishments in all of the categories

listed below.

Table

5-1. Priority Fuel Treatments by

Rank

|

Priority |

Description

|

|

#1 |

Demonstration Projects |

|

#2 |

Treat periphery and wild land inclusions of Bonners

Ferry. |

|

#3 |

Treat fuels around resident schools. |

|

#4 |

Treat fuels around rural homes rated High Risk

where owners are willing. (Includes residences in Naples and Moyie

Springs). |

|

#5 |

Treat fuels around homes rated as moderate risk if

and when funds are available. |